|

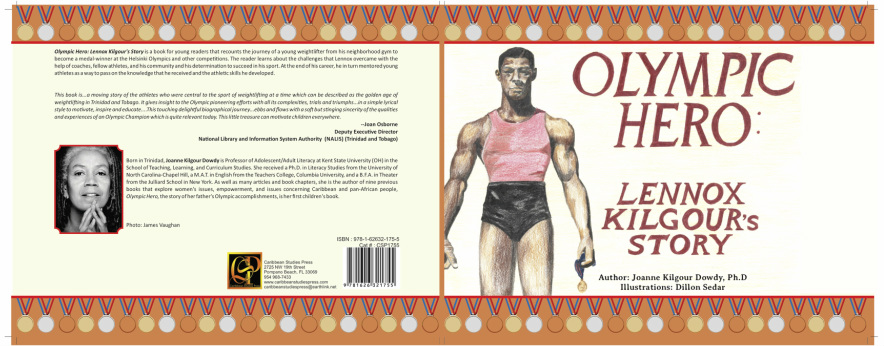

"Lennox Kilgour's Story is a book for young readers that recounts the journey of a young weightlifter from his neighborhood gym to become a medal-winner at the Helsinki Olympics and other competitions. The reader learns about the challenges that Lennox overcame with the help of coaches, fellow athletes, and his community and his determination to succeed in his sport. At the end of his career, he in turn mentored young athletes as a way to pass on the knowledge that he received and the athletic skills he developed.

This book is...a moving story of the athletes who were central to the sport of weightlifting at a time which can be described as the golden age of weightlifting in Trinidad and Tobago. It gives insight to the Olympic pioneering efforts with all its complexies, trials and triumphs...in a simple lyrical style to motivate, inspire and educate....This touching delightful biographical journey...ebbs and flows with a soft but stinging sincerity of the qualities and experiences of an Olympic Champion which is quite relevant today. This little treasure can motivate children everywhere". --Joan Osborne Deputy Executive Director National Library and Information System Authority (NALIS) (Trinidad and Tobago). |

Youtube video of Joanne Kilgour Dowdy reading extracts from her book. |

Olympic Hero : Presentation in Dr. Kist's Class July 15, 2014.

Part 1: Dr. Joanne Kilgour Dowdy

Bill Ki: I feel, I feel fitting our, um, you know, really trying to bring art in on technology this week and multi-modal is the buzzword that is now being used for if we're ever going to talk about that, and all the different terms that are used to talk about this [inaudible 00:00:41] new literacies, multi-literacies, multi-modalities, ICT, I'm trying to go through some digital literacies, digital story telling, these are all terms uses to describe the idea that for most us, we're spending more minutes a day reading in [inaudible 00:01:08] on screens rather than on, on paper. And when we read off the screen, um, we are reading visual imagery and use it for [inaudible 00:01:27] and graphic design, and words of course. Words are still there, it's very important, you can't forget words, but reading and writing are about more words [inaudible 00:01:40].

But, um, so, I'm, that's kind of the purpose of today. We have two gifted artists and we're so honored to have Joanne actually register for this class, she's in [inaudible 00:01:54].

Bill Ki: we've got the speakers, these awesome speakers here today for about an hour or so, and then we'll take a break and then we'll come back and talk about [inaudible 00:02:50].

Joanne:

Bill Kist: Let's give Joanne a round of applause.

Joanne: You can, go on, jkdowdy.com, you can also tweet me at @kilgourJoanne.

Dillon: Do you ever want to start passing out business cards, [crosstalk 00:04:12].

Joanne: . Every time I need something from Dillon, I say Dillon reference the black box.

Bill Ki: Well let me go ahead and do your formal introduction, I don't have to tell you I guess, for er, 14 years now um, you know then when I came [inaudible 00:04:53] campus for sophomore year I got to know her then through the amazing [Nancy Padak] and um, [inaudible 00:05:02] and then when I came to [Kent] campus I was working on, as her next door neighbor, so our offices are right next to each other, and I'm so fortunate to have her as a colleague, she's a gifted artist in so many ways and then I'm always fascinated to hear what her next book idea is or her next video idea is, and she started telling me about this project a few months ago, now [inaudible 00:05:32] Dillon enjoy it, they go all over the place. They were in Oberlin last week doing presentations about this fascinating book. About Joanne's father, so, I don't really know too much about Dillon so I think we're going to learn about you today, [inaudible 00:05:51]. So I'm going to really give you to Joanne and thank you, let's give them a round of applause for being here today.

Joanne: Well, Dr Kist thank you so much for inviting us into this space, I consider this hallowed ground. There's so few places in the institution, and I mean campus life, where multi-modal thinking and teaching is the norm. Where it's celebrated and embraced. I know that because I review portfolios for promotion, and I'm one of the few elders in the [inaudible 00:06:28], I'm a full professor and I get to see portfolios from all over the campuses. So, very few, very few as you were saying Lisa -

Joanne: Very few professors are doing multi-modal instruction or encouraging their teachers, their students to think multi-modally and to perform multi-modally. So I consider this hallowed ground and I really appreciate Dr Kist for allowing me into this space where I am most me. . . . I'm very fortunate to have a colleague and collaborator in Dillon Sedar. I met Dillon in class, he was my student two years ago and I've introduced him to other colleagues. I guess I should stop saying that, my outside life.

Dillon: Oh.

Joanne: Er, Dillon I introduced to other colleagues as the only student in twelve years who understands what I say the first time.

Students: (laughs)

Joanne: It was an amazing, I, it was mind blowing. I would saying once, Dillon was on it. He was explaining to the other students, "She wants you to do this, this, this, this, this." Never had that in twelve years in Ohio. So, I value him tremendously, shut your ears. So um, Dillon is an educator, he's done his first year of full teaching in the [inaudible 00:08:02] public schools.

Dillon: To be determined now, but I taught at . . . and I had the opportunity to [inaudible 00:08:18].

Joanne: And always taught at the detention center?

Dillon: The Southern County Detention Center. Still, still, [inaudible 00:08:22].

Joanne: And is currently painting a mural for those students.

Dillon: Yes, in, er -

Joanne: Social justice has been the organizing theme of our program under Dr Kist for the last four years, we have channeled all our efforts into thinking about how do we do social justice in our classroom? So Dillon exemplifies the kind of colleague I'd want to hire, in that he's not only thinking multi-modally as a visual artist but thinking, "How am I going to reach various audiences?" Because yesterday I said I represent the lower socio-economic group across the country, right? But he had made his career, even before graduating, about the missing voices. The voices we couldn't hear. So they're now- and do they allow them to use technology?

Dillon: No.

Joanne: No. So, that's Dr. Pytash teaches in another, detention center?

Dillon: No, she goes to Southern County.

Joanne: She goes to Southern County? No technology allowed, so, I'm not just running my mouth because I'm the professor, this is a reality in our society. The digital highway is for those who drive on the highway. If you walk on the byroads, you have to have another kind of teacher in your life. Okay? So, that's all to warm you up to where we are, we're going to do three stages of this with a focus on the theme of [multi modal communication]. And in all honesty, as I told Dillon this morning, we are being entirely selfish. We are talking through a paper that we are writing.

So far we have recorded every presentation and transcribed every presentation because we say things on our feet, as you know as teachers, a student asks a question, a light bulb goes on, you never knew you knew that. You never knew you thought that, you never knew you felt that until you are explacating. You're giving them a lot of information. So we are being very selfish where we are thinking through our paper. And, god bless Dr Kist, he is pushing me to embed and I have a lot to embed. Dillon [brought] visuals that I have never seen, he began this project last August, last May, May 15th.

Dillon: May, right.

Joanne: And we could embed, we could embed audio clips of us describing the process or negotiating, I like to say negotiating. Up until last week I was saying, "Dillon and I have fought for a year." (laughs)

Joanne: The politically correct word, is negotiate, [as his grandfather] prompted me one day, on May 22nd, so we're looking at all these pieces of evidence we have about how we collaborated to get to this point. And I have been struggling very hard to figure out, how am I going to tell this story? Because now, in my professional life, I am forced to do the story in print. So that is a challenge, because I think in pictures as you will see and I think in terms of what is the storyboard of this journey. And so Dr Kist giving me this opportunity, I've already asked him to think of my final, what the PhD people are going to be crying and sweating over. Not Beth, because she can do lit reviews like a [senior]. The thing about my paper, the draft towards the professional publication . . ., where am I going to send this news about how two teachers collaborated across disciplines to tell this story? So I won't be doing this much talking and feel free to stop and ask or make or a comment, or let me know you're alive out there, all right, so it's not all about us up here doing the show.

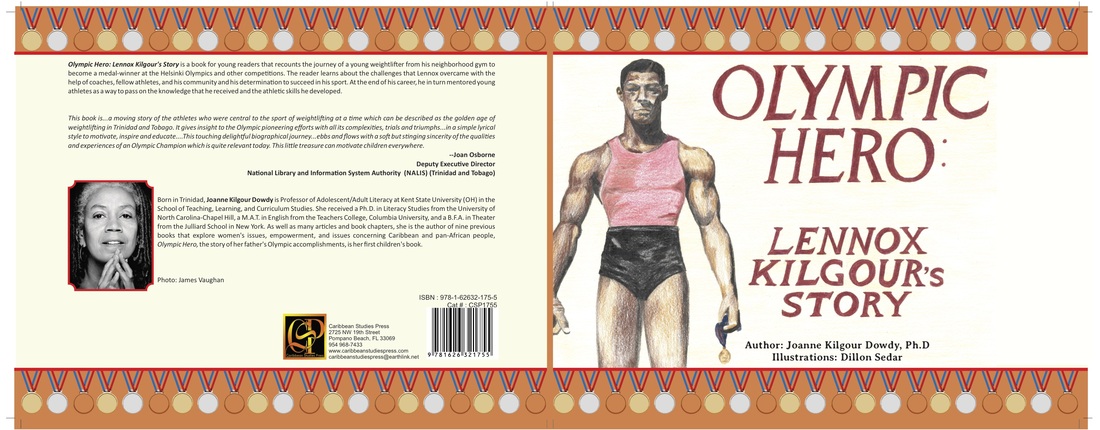

So I want to begin with where this began, December 26th, 2012. I woke up and there was a story in my head, very loud. You know like when you hear the computer go on, you know it's now plugged in, and I was in a panic to get to the computer and start writing. Because I talk about my writing as transcribing. If I don't haer it, I can't write it. I can't write a piece unless there's already a voice going in my head. I'm basically taking notation. So, this, um, [voice] was telling me, "You have to write about your father." [inaudible 00:13:20]. There's only one book written about the Olympians from Trinidad.

|

One book. Fortunately I have it in my collection, I had to go find it. . . . My office is a work of art.

Bill Kist: (laughs) Joanne: So I had to go find this, and because we're dealing with symbol systems, I wanted to see [inaudible 00:13:47], this is just one of the chapters of [THE OLYMPIANS]. And, we're dealing with this visually so please don't try to read this. I just want you to see what the map looks like. |

So how will you describe this visual presentation on the page? What are the features that jump out at you? It's not a test, remember I'm thinking through my paper. So visually, when you pick it up, what do you notice? If you're a designer, like Dillon is. If I tell Dillon, "Dillon take this, make it look something like this." What features enclosed am I asking him to imitate? Without reading.

Lisa: Text?

Joanne: Text. So use text, why? Use words, remember in this class we're saying text is all kinds of communication symbols. So, use words, right, what else Lisa am I asking him to imitate?

Student: The title.

Joanne: Title. Use a bold font title so it stands out. Any other feature [inaudible 00:14:57]?

Student: Very linear.

Joanne: Very linear, right. So we know that it's going . . . . horizontal. . . . when you were growing up, you know when TV signed off at midnight, there were lines that went across the screen. Unfortunately if you die there's a line that goes across the screen, right? So it's a blank line. Any other feature that you notice about this piece of communication?

Speaker 8: [inaudible 00:15:25].

Speaker 4: Very simple, very corporate at least.

Joanne: The [inaudible 00:15:26] of the spread, the designer has that in his head. So what's in his head? Ahmad?

Adam: He uses the page numbers.

Joanne: Page numbers, [inaudible 00:15:34] the design, right, anything else, Kayla?

Kayla: Um, the almost [inaudible 00:15:41].

Joanne: Okay, so there's a number that indicates that this is coming in some kind of serial, like we lined up in our [exercise with Dr. Kist] right? So there's a definite organization, yes. Go ahead, Caitlyn.

Caitlyn: Well, he's, the author's just showing it protects the life of illustrations.

Joanne: No, illustrations just through text. Now do you realize that the text comes in what? Blocks, blocks. So you see teachers, because you are so brilliant at reading the samples, that you forget that someone who does not read this language is looking at text features. Okay? So you're helping me think this through, that's what I like about this. So when I ask you, "Look at this." Or "Look at the text features." You're pressing, because you want to get to, "What is it saying, what is it saying?" But if I'm locked out, if it's Chinese, I'm looking at text features for some clue to get me in, yes? You're saying yes. You . . . , [inaudible 00:16:49]. So what language do you read or [inaudible 00:16:49]? English of course. Students who are, I mean who are, locked by language background. Are there any in your classroom?

Student: I had a student, Sophia -

Joanne: Yes.

Student: So er, [inaudible 00:17:04]. . . . this year made it. . . . for her -

Joanne: So all you're seeing is those text features, those organizational features that we take for granted. We pick up that page and we say, "Ooo! This is a page from a book." Yeah, because we've been doing this so long we don't have to think about what it represents, that's a brilliant idea.

Beth: One of the things that, I don't know if you will have been yet, but when I think about [inaudible 00:17:27], I feel very, long and distant, you know, so, that's, . . . feelings to me. Even without reading it out you're still, it's full of facts.

Joanne: Okay. So you're on the sixth floor of the building right? So imagine you start on the first floor and you're way up, you're saying now tone and intention.

Beth: Yeah. Just by looking at it.

Joanne: Just by looking at it, so you have enough experience with it to, to start reading into, what might I get? Every method gives me something, so I'd go with very selfish intentions. What am I going to get, what's in it for me? All reading is about it. WIFM, What's In It For Me, I'm going to get something. So here's something I read a couple of weeks ago, and this is by a Hindu Monastic, I'm not doing religion. Just showing how my brain is wired to look for symbol systems, okay he was here in the 1800s, and they documented all his lectures. So he's in Chicago at what was called the Parliament of Religions [view image here].

Lisa: Text?

Joanne: Text. So use text, why? Use words, remember in this class we're saying text is all kinds of communication symbols. So, use words, right, what else Lisa am I asking him to imitate?

Student: The title.

Joanne: Title. Use a bold font title so it stands out. Any other feature [inaudible 00:14:57]?

Student: Very linear.

Joanne: Very linear, right. So we know that it's going . . . . horizontal. . . . when you were growing up, you know when TV signed off at midnight, there were lines that went across the screen. Unfortunately if you die there's a line that goes across the screen, right? So it's a blank line. Any other feature that you notice about this piece of communication?

Speaker 8: [inaudible 00:15:25].

Speaker 4: Very simple, very corporate at least.

Joanne: The [inaudible 00:15:26] of the spread, the designer has that in his head. So what's in his head? Ahmad?

Adam: He uses the page numbers.

Joanne: Page numbers, [inaudible 00:15:34] the design, right, anything else, Kayla?

Kayla: Um, the almost [inaudible 00:15:41].

Joanne: Okay, so there's a number that indicates that this is coming in some kind of serial, like we lined up in our [exercise with Dr. Kist] right? So there's a definite organization, yes. Go ahead, Caitlyn.

Caitlyn: Well, he's, the author's just showing it protects the life of illustrations.

Joanne: No, illustrations just through text. Now do you realize that the text comes in what? Blocks, blocks. So you see teachers, because you are so brilliant at reading the samples, that you forget that someone who does not read this language is looking at text features. Okay? So you're helping me think this through, that's what I like about this. So when I ask you, "Look at this." Or "Look at the text features." You're pressing, because you want to get to, "What is it saying, what is it saying?" But if I'm locked out, if it's Chinese, I'm looking at text features for some clue to get me in, yes? You're saying yes. You . . . , [inaudible 00:16:49]. So what language do you read or [inaudible 00:16:49]? English of course. Students who are, I mean who are, locked by language background. Are there any in your classroom?

Student: I had a student, Sophia -

Joanne: Yes.

Student: So er, [inaudible 00:17:04]. . . . this year made it. . . . for her -

Joanne: So all you're seeing is those text features, those organizational features that we take for granted. We pick up that page and we say, "Ooo! This is a page from a book." Yeah, because we've been doing this so long we don't have to think about what it represents, that's a brilliant idea.

Beth: One of the things that, I don't know if you will have been yet, but when I think about [inaudible 00:17:27], I feel very, long and distant, you know, so, that's, . . . feelings to me. Even without reading it out you're still, it's full of facts.

Joanne: Okay. So you're on the sixth floor of the building right? So imagine you start on the first floor and you're way up, you're saying now tone and intention.

Beth: Yeah. Just by looking at it.

Joanne: Just by looking at it, so you have enough experience with it to, to start reading into, what might I get? Every method gives me something, so I'd go with very selfish intentions. What am I going to get, what's in it for me? All reading is about it. WIFM, What's In It For Me, I'm going to get something. So here's something I read a couple of weeks ago, and this is by a Hindu Monastic, I'm not doing religion. Just showing how my brain is wired to look for symbol systems, okay he was here in the 1800s, and they documented all his lectures. So he's in Chicago at what was called the Parliament of Religions [view image here].

Very famous, if you read any literature on the transformation of America from a one religion society to a multi-religion society. So we have evolved over 200 years to using multiple symbols, that's why when you drive along and you see the person with the, with the Christian symbol, the Hindu symbol, that's because it took us 200 years to get to this point. Starting at this point.

So just this first sentence, “in one sense we cannot think but in symbols. Words themselves are symbols of thought, in another sense everything in the universe may be looked upon as a symbol. The whole universe is a symbol.” And then another sentence, “ in old Babylon and in Egypt, it was to be found, these symbols. What does it show? All these symbols cannot have been purely conventional, there must be some reasons for them. Some natural association between them and the human mind. Language is not the result of convention, it's not that people have ever agreed to represent certain ideas by certain words. There never was an idea without a corresponding word or a word without a corresponding idea. Ideas and words are . . . naturally inseparable.” So I have just found the opening for my journal publication. Ideas and words are inseparable.”

So I go for a [inaudible 00:20:14] distant text that best describes, and I go to this version. So I have taken the author's chapter and this is what I said to my colleague who writes [inaudible 00:20:31] books. Notice I'm using the writer's process. Because, I am going to condense research and this is something you want your students to do. You don't want them to spit back what they found in the encyclopedia. You want them now to put it in their words. So again, don't try to read it teachers. I see you jumping in your Mercedes, [and speeding] down. [ROUTE] 76. Look at the form, what has happened from the first version text features to this version? First thing that jumps out at you? Yes, Caitlyn?

Caitlyn: Very smaller boxes.

Joanne: Smaller boxes, what else jumps out at you? Kayla?

Kayla: Um, the title is a little more bigger than -

Joanne: They've become a little bit more user friendly.

Student: Just the way the wording is.

Joanne: Okay.

Student: Say you're coming from a [inaudible 00:21:29] industries background, identifying the words you can hear are more readily -

Joanne: Then the first version, that is loud, bold. Okay, anything else? Yes, thank you.

Speaker 8: Color.

Joanne: Color. Color changed, so now I'm in a different color. Anything else that, yes, there.

Speaker 12: I noticed you know, the [inaudible 00:21:51] it's like organized better, [inaudible 00:21:56].

Joanne: Okay. So it's organized . . . . So something [crosstalk 00:22:01]

Speaker 12: Timeline, so you come in and -

Joanne: Timeline, right. So you have penetrated the author's organizing system. Yes, but if you made a timeline, going from the chapter where he gives me lots of details that every single day of this journey, to what's Lennoxs' story. I want the beginning, middle and end. I'm a very beginning, middle and end person. Dillon heard that, ad infanitum, he's nodding his head. So I asked Dillon to turn poems into story form, and this is one student's interpretation of a poem by a famous Cleveland poet, Mary Weems. Now this is what one student came up with. Beginning, middle and end, because we in the west are wired for beginning, middle and end. Right? Our lines, [that we created in Dr. Kist's exercise] suddenly January ends in December. We are wired, we are looking for a beginning, middle and end all the time. Even if, even if, in that famous classic film, December was put up front, we still know that's an end, and my brain's going to figure out how that end is the summation of the story. Because we have that need to do those three pieces.

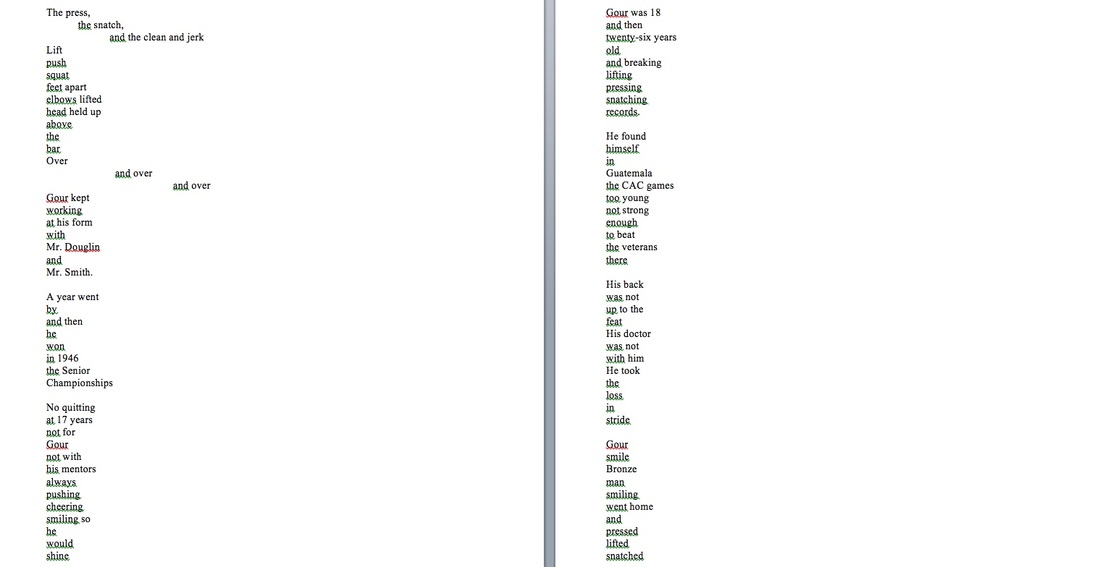

Okay, so, moving on to this version. Tell me what you notice in this version. And I promise this is the end of talky talky, next you're going to have the visual artist. And then there's more talky talky. But you have the real deal. So, what do you see now happening in this version? What's the, what's the writer doing now? Remember I'm transcribing, I'm taking the voice in my head and getting it on the page as fast as I can. So what's happened here. April?

April: Graphic numbers.

Joanne: Partners and numbers, what else happened here?

Joanne: Yes, [inaudible 00:24:18], what else?

Kayla: There's more space in between them.

Joanne: More space in between, what else?

Lisa: It's green. (laughs)

Joanne: It's green. So, on that note, it's called, that's Dillon's input from me, come on [Dowdy], is anything else happening in this little short, short shots [inaudible 00:24:42]?

Adam: Well they look like topic sentences.

Joanne: Topic sentences, but you're reading, you're going into words, right? I want you to

Ahmad: No.

Joanne: No?

Adam: The reason I say that is because -

Joanne: Uh-huh (affirmative)

Ahmad: There's so much space between them.

Joanne: Oh, there's so much space in between, right. Okay, so at this point we go to my visual artist friend. And I say, "I want you to show me," Let's take one and pass the others so every has a visual in front of them

So just this first sentence, “in one sense we cannot think but in symbols. Words themselves are symbols of thought, in another sense everything in the universe may be looked upon as a symbol. The whole universe is a symbol.” And then another sentence, “ in old Babylon and in Egypt, it was to be found, these symbols. What does it show? All these symbols cannot have been purely conventional, there must be some reasons for them. Some natural association between them and the human mind. Language is not the result of convention, it's not that people have ever agreed to represent certain ideas by certain words. There never was an idea without a corresponding word or a word without a corresponding idea. Ideas and words are . . . naturally inseparable.” So I have just found the opening for my journal publication. Ideas and words are inseparable.”

So I go for a [inaudible 00:20:14] distant text that best describes, and I go to this version. So I have taken the author's chapter and this is what I said to my colleague who writes [inaudible 00:20:31] books. Notice I'm using the writer's process. Because, I am going to condense research and this is something you want your students to do. You don't want them to spit back what they found in the encyclopedia. You want them now to put it in their words. So again, don't try to read it teachers. I see you jumping in your Mercedes, [and speeding] down. [ROUTE] 76. Look at the form, what has happened from the first version text features to this version? First thing that jumps out at you? Yes, Caitlyn?

Caitlyn: Very smaller boxes.

Joanne: Smaller boxes, what else jumps out at you? Kayla?

Kayla: Um, the title is a little more bigger than -

Joanne: They've become a little bit more user friendly.

Student: Just the way the wording is.

Joanne: Okay.

Student: Say you're coming from a [inaudible 00:21:29] industries background, identifying the words you can hear are more readily -

Joanne: Then the first version, that is loud, bold. Okay, anything else? Yes, thank you.

Speaker 8: Color.

Joanne: Color. Color changed, so now I'm in a different color. Anything else that, yes, there.

Speaker 12: I noticed you know, the [inaudible 00:21:51] it's like organized better, [inaudible 00:21:56].

Joanne: Okay. So it's organized . . . . So something [crosstalk 00:22:01]

Speaker 12: Timeline, so you come in and -

Joanne: Timeline, right. So you have penetrated the author's organizing system. Yes, but if you made a timeline, going from the chapter where he gives me lots of details that every single day of this journey, to what's Lennoxs' story. I want the beginning, middle and end. I'm a very beginning, middle and end person. Dillon heard that, ad infanitum, he's nodding his head. So I asked Dillon to turn poems into story form, and this is one student's interpretation of a poem by a famous Cleveland poet, Mary Weems. Now this is what one student came up with. Beginning, middle and end, because we in the west are wired for beginning, middle and end. Right? Our lines, [that we created in Dr. Kist's exercise] suddenly January ends in December. We are wired, we are looking for a beginning, middle and end all the time. Even if, even if, in that famous classic film, December was put up front, we still know that's an end, and my brain's going to figure out how that end is the summation of the story. Because we have that need to do those three pieces.

Okay, so, moving on to this version. Tell me what you notice in this version. And I promise this is the end of talky talky, next you're going to have the visual artist. And then there's more talky talky. But you have the real deal. So, what do you see now happening in this version? What's the, what's the writer doing now? Remember I'm transcribing, I'm taking the voice in my head and getting it on the page as fast as I can. So what's happened here. April?

April: Graphic numbers.

Joanne: Partners and numbers, what else happened here?

Joanne: Yes, [inaudible 00:24:18], what else?

Kayla: There's more space in between them.

Joanne: More space in between, what else?

Lisa: It's green. (laughs)

Joanne: It's green. So, on that note, it's called, that's Dillon's input from me, come on [Dowdy], is anything else happening in this little short, short shots [inaudible 00:24:42]?

Adam: Well they look like topic sentences.

Joanne: Topic sentences, but you're reading, you're going into words, right? I want you to

Ahmad: No.

Joanne: No?

Adam: The reason I say that is because -

Joanne: Uh-huh (affirmative)

Ahmad: There's so much space between them.

Joanne: Oh, there's so much space in between, right. Okay, so at this point we go to my visual artist friend. And I say, "I want you to show me," Let's take one and pass the others so every has a visual in front of them

I go to my visual artist and I say, "I want you to show me what you see." So it's all in my head right, that's whats wrong with artists, we're all crazy, it's all in our head. We want to get it out of our head, so I got to my visual artist and I say, "Look, this is what I have in print, I want to see what you get out. Do you see what I see?"

Dr. Kist: And that's when you [give the manuscript to Dillon] this?

Joanne: Good, [inaudible 00:25:38]. I gave her, [inaudible 00:25:40]. (laughs)

Dr. Kist: You gave to her.

Joanne: I gave to her the green version.

Dr. Kist: Green version.

Joanne: Green version. I worked through my process and now she has the green version. Does everyone have the handout in front of them, just pass the, one underneath, it's okay [inaudible 00:25:58]. I just want you to see now what has happened in our multi-modal environment, that I go from print to this visual, a lot of visual symbols. So if you exchange these pagers, Ahmad is doing without any paper, Ahmad hasn't had anything.

Ahmad: Oh, I have, I passed it on.

Joanne: Oh, I thought you were, I want everyone to have something in their hand. I'm very into kinesthetics. And I want you to feel it's yours. Okay, so now you have this new version. And remember, because I'm a filmmaker, I'm always thinking the storyboard. I know the storyboard, I want to talk about, but those spaces in that green page are now filled with these images. So, on my computer I now have text on one side, print, and text on the right side, this image. This is now my draft. This is what I send to a publisher and say, I have an idea for a book. Here's a draft, all right.

Dr. Kist: And that's when you [give the manuscript to Dillon] this?

Joanne: Good, [inaudible 00:25:38]. I gave her, [inaudible 00:25:40]. (laughs)

Dr. Kist: You gave to her.

Joanne: I gave to her the green version.

Dr. Kist: Green version.

Joanne: Green version. I worked through my process and now she has the green version. Does everyone have the handout in front of them, just pass the, one underneath, it's okay [inaudible 00:25:58]. I just want you to see now what has happened in our multi-modal environment, that I go from print to this visual, a lot of visual symbols. So if you exchange these pagers, Ahmad is doing without any paper, Ahmad hasn't had anything.

Ahmad: Oh, I have, I passed it on.

Joanne: Oh, I thought you were, I want everyone to have something in their hand. I'm very into kinesthetics. And I want you to feel it's yours. Okay, so now you have this new version. And remember, because I'm a filmmaker, I'm always thinking the storyboard. I know the storyboard, I want to talk about, but those spaces in that green page are now filled with these images. So, on my computer I now have text on one side, print, and text on the right side, this image. This is now my draft. This is what I send to a publisher and say, I have an idea for a book. Here's a draft, all right.

Adam: With these pictures?

Joanne: No, no pictures.

Adam: No pictures.

Joanne: Because I don't have permission to publish those, to send those beyond my little relationship with my, visual artist, and she is deciding, "Do I want to do this job?" Let me tell you, I went through six artists before Dillon arrived on my doorstep. You know when they say. what you need is right at home, and you go abroad. Six people turned me down because it was too much. They would have to invent too much to pull this off. So finally I sent email to my art educator professors and said, "Help!" With sixteen exclamation points.

Dillon: No joke.

(laughs)

Joanne: He saw it. "I need an illustrator, NOW" In capital letters, and that day I got goosebumps, Dillon called and said, "I want the job." [inaudible 00:28:08]. That was a divine intervention. I have talked about this journey as a divine experience from get go. From me hearing voices, you know, I look crazy. I'll admit it, probably to Dillon arriving, just after school, he'll tell you his story. So that is the script part of this journey. This is the writing process that got me to the place where I'm able to hand Dillon, after my two writing friends, I'm taking up all the copies, [inaudible 00:28:48], they have been through that, all of it, you name it. So this is the version Dillon gets. He'll tell you his reaction to this, [inaudible 00:28:59] on the page. What do you see Caitlyn?

Caitlyn: Um, it's very, I guess vertical versus horizontal.

Joanne: All right, gone from horizontal slack line dead, no blood, the monitor shuts off, and now it's going from top to bottom. Huge transition, that's after my writer friends gave me a list of children books to read, and I read all the Caldecott from 1957 to 2013. Word to the wise, you can't write in a context that you don't understand. If you're going to write a dissertation, read twelve. If you're going to write an article for Times Magazine, read 200 Times Magazine articles. And I'm like, "Can I make films if you've never learned from films?" I'm always sending film notices to Dr. Kist because [film is] a language, I'm always sending my notices. Dillon says he doesn't do the New York Times, but I send him so much he thinks he's actually got a subscription to the paper (laughs). He knows everything happening around the world because I read the New York Times titles, and I click and send him notices.

Dillon: Did you say why though that you wanted to make this a children's book? Did you say that yet?

Joanne: I have planned for 10 years to write a children's book. I never knew what the topic would be. I have been to all the Virginia Hamilton conferences to listen to writers, to look at illustrators, I have collected children's books, so now I've got like a library of children's books. Dillon will tell you about him experiencing that. I just know, if you want to write in a genre you better be so immersed in that genre that it's just sweating out of you like, without you even thinking.

So I bought a children's book written about Bob Marley and it was written in verse, and it just turned that dial into extra hot. And, the next morning I woke up, I heard the story, the way it's written on this last version. Top to bottom, I heard it. I was racing to write it, and I promised myself to write one insert per day. Nothing more. Anything more was me trying to guide the process. I wanted the process to guide me, the process said, "You will do one insert per day." So at 7AM, I sat down, I just type, and then I closed the file and left.

KIST: One insert?

Joanne: One insert. One insert. Just one of those per day, don't look back, don't touch it, don't fuss. Because my academic mind was going to start taking over. Analyzing and fidgeting and wanting it to look like, you know, like it was real from protocol writing, whatever that was supposed to be. So, this is what Dillon got. So I went to Dillon, that's my story, I'm throwing to you.

Joanne: No, no pictures.

Adam: No pictures.

Joanne: Because I don't have permission to publish those, to send those beyond my little relationship with my, visual artist, and she is deciding, "Do I want to do this job?" Let me tell you, I went through six artists before Dillon arrived on my doorstep. You know when they say. what you need is right at home, and you go abroad. Six people turned me down because it was too much. They would have to invent too much to pull this off. So finally I sent email to my art educator professors and said, "Help!" With sixteen exclamation points.

Dillon: No joke.

(laughs)

Joanne: He saw it. "I need an illustrator, NOW" In capital letters, and that day I got goosebumps, Dillon called and said, "I want the job." [inaudible 00:28:08]. That was a divine intervention. I have talked about this journey as a divine experience from get go. From me hearing voices, you know, I look crazy. I'll admit it, probably to Dillon arriving, just after school, he'll tell you his story. So that is the script part of this journey. This is the writing process that got me to the place where I'm able to hand Dillon, after my two writing friends, I'm taking up all the copies, [inaudible 00:28:48], they have been through that, all of it, you name it. So this is the version Dillon gets. He'll tell you his reaction to this, [inaudible 00:28:59] on the page. What do you see Caitlyn?

Caitlyn: Um, it's very, I guess vertical versus horizontal.

Joanne: All right, gone from horizontal slack line dead, no blood, the monitor shuts off, and now it's going from top to bottom. Huge transition, that's after my writer friends gave me a list of children books to read, and I read all the Caldecott from 1957 to 2013. Word to the wise, you can't write in a context that you don't understand. If you're going to write a dissertation, read twelve. If you're going to write an article for Times Magazine, read 200 Times Magazine articles. And I'm like, "Can I make films if you've never learned from films?" I'm always sending film notices to Dr. Kist because [film is] a language, I'm always sending my notices. Dillon says he doesn't do the New York Times, but I send him so much he thinks he's actually got a subscription to the paper (laughs). He knows everything happening around the world because I read the New York Times titles, and I click and send him notices.

Dillon: Did you say why though that you wanted to make this a children's book? Did you say that yet?

Joanne: I have planned for 10 years to write a children's book. I never knew what the topic would be. I have been to all the Virginia Hamilton conferences to listen to writers, to look at illustrators, I have collected children's books, so now I've got like a library of children's books. Dillon will tell you about him experiencing that. I just know, if you want to write in a genre you better be so immersed in that genre that it's just sweating out of you like, without you even thinking.

So I bought a children's book written about Bob Marley and it was written in verse, and it just turned that dial into extra hot. And, the next morning I woke up, I heard the story, the way it's written on this last version. Top to bottom, I heard it. I was racing to write it, and I promised myself to write one insert per day. Nothing more. Anything more was me trying to guide the process. I wanted the process to guide me, the process said, "You will do one insert per day." So at 7AM, I sat down, I just type, and then I closed the file and left.

KIST: One insert?

Joanne: One insert. One insert. Just one of those per day, don't look back, don't touch it, don't fuss. Because my academic mind was going to start taking over. Analyzing and fidgeting and wanting it to look like, you know, like it was real from protocol writing, whatever that was supposed to be. So, this is what Dillon got. So I went to Dillon, that's my story, I'm throwing to you.

Part 2: Dillon Sedar

Dillon: Okay, thank you. I, I will say, quickly, I tend to go quickly. So if you happen to have any questions or concerns please do not hesitate to ask me while I go on. Um, because there is a lot that I'm going to do, because I wanted to make sure I covered all bases, okay? So, my story. I graduated from Penn State, in Art Education, May 2013. Went home, uh, what to do was kind of scary because I wasn't sure what my future held at that time. Didn't have a job in line, uh, I just knew I was going to apply, apply, apply but this story isn't much about my professional career, my education. I want to express to you that I went home and I found out that I didn't have my lovely summer, what was my title ... I can't remember, maybe it'll come to me.

But it was a person to the value of stock-boy, thank you, stock-boy in a pool place that wasn't available anymore. So, I didn't have a summer job, I didn't have a future, um, I had a budget future in mind but I didn't have a concrete future in mind, something to work for. So, like Joanne said, I got an email soon after I graduated, immediately after I graduated, that said "I need an illustrator now." And I called her, and she had said that I was in class with her before, and to this day, I love this story, it's hilarious. I called her, calling about three times, when I said "Hello." Joanne said, "DILLON, you can't get rid of me can you?"

Joanne: (laughs)

Dillon: And I said, "No I guess not, I'm going to be your illustrator." So, I began this journey, never had I done an illustration job in my life, I have illustrative skills, I had, I'd done a character for my own um, my artwork, my personal practice is always side along. My personal practice has always been about character. I've always had an interest in character, I had an interest in emotion and how people interact with each other, how people interact with artwork and therefore a lot of my artwork has to do with character.

But it was a person to the value of stock-boy, thank you, stock-boy in a pool place that wasn't available anymore. So, I didn't have a summer job, I didn't have a future, um, I had a budget future in mind but I didn't have a concrete future in mind, something to work for. So, like Joanne said, I got an email soon after I graduated, immediately after I graduated, that said "I need an illustrator now." And I called her, and she had said that I was in class with her before, and to this day, I love this story, it's hilarious. I called her, calling about three times, when I said "Hello." Joanne said, "DILLON, you can't get rid of me can you?"

Joanne: (laughs)

Dillon: And I said, "No I guess not, I'm going to be your illustrator." So, I began this journey, never had I done an illustration job in my life, I have illustrative skills, I had, I'd done a character for my own um, my artwork, my personal practice is always side along. My personal practice has always been about character. I've always had an interest in character, I had an interest in emotion and how people interact with each other, how people interact with artwork and therefore a lot of my artwork has to do with character.

So I had an idea of a character in my head, a well rounded portfolio that my professor was working on and, and, [inaudible 00:34:33] showed me or recommended me to go in. Um, so, from there I did receive what we see now is the final manuscript And when I looked at this, I just thought, "Okay, Joanne is crazy, this is like a typo or Word document, margins were messed up." She just typed it out, went "Okay. I'm done with it."

Joanne: (laughs) That too.

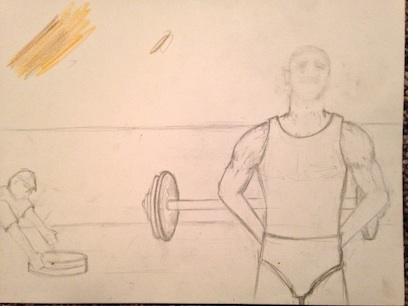

Dillon: I think a quarter of the way through the experience I realized that this was untouchable. This was meant to be poetic, she wrote it that way, in that format because that visual was, oh I should have been talking to you. Presents a different method of reading to you. If it was linear and you could just fly through it, that's it. But since it's in poetic, since it's in verse, I should say, it makes you saw appreciate looked, look at each individual word [inaudible 00:35:36]. Um, so from there, I started writing a story. I had a copy of the individual manuscript. You'll see some of the pages, today I brought with me, and you're lucky because I haven’t presented this yet. And Joanne will be seeing some of these for the first time.

These are, these are somewhat outtakes for the process of trying to get the final look, the final illustrations [inaudible 00:36:06] and what I wanted to say is that Joanne was talking about collaboration and how we collaborated on this. And I think what is beautiful about this is that [inaudible 00:36:20] Because we had [inaudible 00:36:26] we didn't need to help. The words would mean one thing to her, another thing to me. Through words, all she did the pure essence that she was looking for in the book. She had broken, that was my term, to give it a visual. So we had to work very hard, nearly, back and forth daily, on a daily basis, to get this last stuff made to art. Worked very hard.

But, what I'd like to do, I have, I set, I set aside the individual images I'll start with. I'll show you the final process or the final product of that, so you can see what happened, right? Um, I want you to pass some of these around. I had about 200 this year, [inaudible 00:37:18].

[View image here]

Dillon: I think a quarter of the way through the experience I realized that this was untouchable. This was meant to be poetic, she wrote it that way, in that format because that visual was, oh I should have been talking to you. Presents a different method of reading to you. If it was linear and you could just fly through it, that's it. But since it's in poetic, since it's in verse, I should say, it makes you saw appreciate looked, look at each individual word [inaudible 00:35:36]. Um, so from there, I started writing a story. I had a copy of the individual manuscript. You'll see some of the pages, today I brought with me, and you're lucky because I haven’t presented this yet. And Joanne will be seeing some of these for the first time.

These are, these are somewhat outtakes for the process of trying to get the final look, the final illustrations [inaudible 00:36:06] and what I wanted to say is that Joanne was talking about collaboration and how we collaborated on this. And I think what is beautiful about this is that [inaudible 00:36:20] Because we had [inaudible 00:36:26] we didn't need to help. The words would mean one thing to her, another thing to me. Through words, all she did the pure essence that she was looking for in the book. She had broken, that was my term, to give it a visual. So we had to work very hard, nearly, back and forth daily, on a daily basis, to get this last stuff made to art. Worked very hard.

But, what I'd like to do, I have, I set, I set aside the individual images I'll start with. I'll show you the final process or the final product of that, so you can see what happened, right? Um, I want you to pass some of these around. I had about 200 this year, [inaudible 00:37:18].

[View image here]

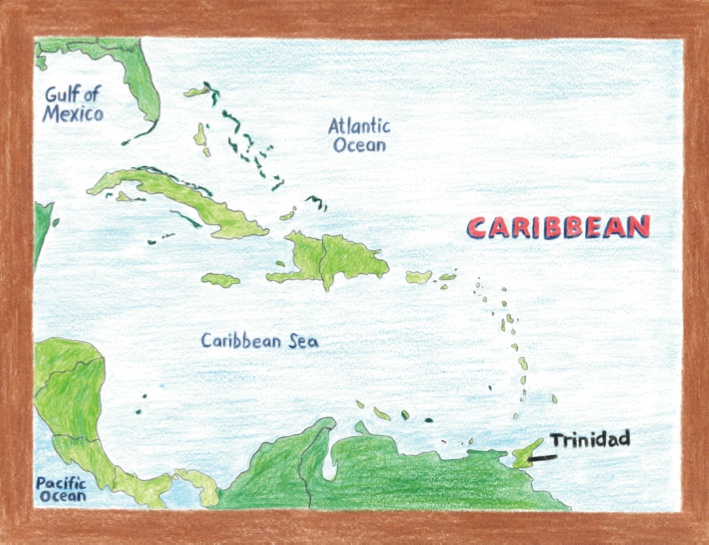

So make sure everyone gets a chance to see this. At this point in the process, I went into illustration, I had a very stereotypical view of what a children's book should be. I was thinking, "Okay, it's a children's story without her father, great, I can just make a little cartoon, started weight lifting, it would be color friendly, colorful and that will be it, that should be, I can do that."

So, in my mind, I had an idea that this is going to be a representation of her father. Not her father himself, just something that would represent him, even if it doesn't look like him, and I had a very stubborn kind of idea of what this should be. More about me, like, "Oh, I would want to do this." And as you can see in this image in particular, here, [inaudible 00:38:17]. This one, and actually the colored one as well, both of these, I thought this was meant to be a representation. I was going to draw a character that could be Lennox, and then I'll keep it consistent throughout the book. But Joanne was about to say, "No, it's not. I need likeness. I need to see my father, these were not him."

So what she said that, then after we got to this one in particular, in which I tried to depict his face after very, [inaudible 00:38:53]. So I had, I then took on the task, "Okay, I've see LenNox, I've seen photos of him." Now I had to try to depict the face on my own, which I'm, oh I'm glad you can see the, many a raised eyebrow looking at me, but, that that's impossible. You need to, well, it may be possible, but it's hard to see somebody's face, maybe say this one, and then transform that face into, a [inaudible 00:39:30] this is an important one where he hurt his back. Now, what I want to do ... What I want to do is show you the file, and tell you what decisions I made and why. There we go.

So, in my mind, I had an idea that this is going to be a representation of her father. Not her father himself, just something that would represent him, even if it doesn't look like him, and I had a very stubborn kind of idea of what this should be. More about me, like, "Oh, I would want to do this." And as you can see in this image in particular, here, [inaudible 00:38:17]. This one, and actually the colored one as well, both of these, I thought this was meant to be a representation. I was going to draw a character that could be Lennox, and then I'll keep it consistent throughout the book. But Joanne was about to say, "No, it's not. I need likeness. I need to see my father, these were not him."

So what she said that, then after we got to this one in particular, in which I tried to depict his face after very, [inaudible 00:38:53]. So I had, I then took on the task, "Okay, I've see LenNox, I've seen photos of him." Now I had to try to depict the face on my own, which I'm, oh I'm glad you can see the, many a raised eyebrow looking at me, but, that that's impossible. You need to, well, it may be possible, but it's hard to see somebody's face, maybe say this one, and then transform that face into, a [inaudible 00:39:30] this is an important one where he hurt his back. Now, what I want to do ... What I want to do is show you the file, and tell you what decisions I made and why. There we go.

Lisa: [inaudible 00:40:00].

Dillon: Yes, these are the, these are the file images that [inaudible 00:40:05] warned you of before. But this image in particular was the file image I chose from one English [inaudible 00:40:11] and what I eventually ended up doing, as I say I gave up on the face, I didn't try to depict his face, but instead I had him hunched over, I actually found a runner, an Olympic runner that was injured, in this kind of position and I referenced that, it just kind of ran away with itself. And, I add more, I added more muscles on obviously because runners have a more athletic stance, you know they're very, well, I, I guess slimmer, right? Way less [inaudible 00:40:45] in which Lenox was. So that's, those were my files, um, yeah. [inaudible 00:40:54]. Um, I had a couple of files here, from her. These are not referencing the same images what that was. So let's pass these around, [inaudible 00:41:05].

Dillon: Yes, these are the, these are the file images that [inaudible 00:40:05] warned you of before. But this image in particular was the file image I chose from one English [inaudible 00:40:11] and what I eventually ended up doing, as I say I gave up on the face, I didn't try to depict his face, but instead I had him hunched over, I actually found a runner, an Olympic runner that was injured, in this kind of position and I referenced that, it just kind of ran away with itself. And, I add more, I added more muscles on obviously because runners have a more athletic stance, you know they're very, well, I, I guess slimmer, right? Way less [inaudible 00:40:45] in which Lenox was. So that's, those were my files, um, yeah. [inaudible 00:40:54]. Um, I had a couple of files here, from her. These are not referencing the same images what that was. So let's pass these around, [inaudible 00:41:05].

Because we wanted to represent LenNox realistically, wanted him to be Lenox. I thought, "Okay," again, being very amateur in illustration, I thought, "You know, I have a bunch of pictures with Joanne, who looks a lot like her father, when she was younger and you know, [inaudible 00:41:33] at the age at the time, that maybe I'll reference her face." So, as you can see on that tracing paper, I literally took a picture of Joanne and traced her face, tried to give it a more male form and you know, sculpted shorter hair and [inaudible 00:41:49]. Sent her away and still, no. That's not it.

Adam: When you sent it her way was it electronically?

Dillon: Yes.

Joanne: Yes, all -

Dillon: All electronic.

Joanne: And when Joel faces me [crosstalk 00:42:04]

Dillon: Then you see my boss. Very easy with an iPhone to take, er, a high resolution picture and, those of you that have iPhones may know, it's very easy to take a photo and send it via email easily. So I already [inaudible 00:42:20] the image that night, take a picture, send it, go to sleep and pray that it was accepted in the morning. Or, [inaudible 00:42:29] which is okay, and the way, this is quite a beautiful thing too is that, the way my work schedule was, [inaudible 00:42:37], if I was only doing this I really, it might have driven me mad. If I was only doing this, but I did, I did find a part time job, I worked at a warehouse so it was very mundane, very [inaudible 00:42:52]. But, for that whole time, now that [inaudible 00:43:02]. It gave me a chance to fulfill that visual in my mind, based upon what she said. Sometimes I'd get emails with files that work, check, check the lunch break which was fine. I would check during lunch break and I would see, and it would help, it would just help.

The more she communicated with me, the better it was for me to build that visual. So I build that visual, I built a lot of visuals, based upon that. Um, so I realized with this especially that Joanne's facials weren't going to work, that I really just needed to use his face, use the photographs that we had, were very valuable. You'll see in the book and in the film, that there's a lot of instances where there's um, I'm giving away my process but that's okay, is that, the images that really do look like him were referenced from photographs. If you ever get, there are some images where you can only see the back of his head, or like in action and those are stuff that I had to kind of create myself, but yeah, he, in some cases. Um, I will, I will show this one I was holding so you can see. This, this you can see the difference. Huge difference. Can almost point out, I really captured the youth in him. [inaudible 00:44:29]. No, no -

Dillon: Yes.

Joanne: Yes, all -

Dillon: All electronic.

Joanne: And when Joel faces me [crosstalk 00:42:04]

Dillon: Then you see my boss. Very easy with an iPhone to take, er, a high resolution picture and, those of you that have iPhones may know, it's very easy to take a photo and send it via email easily. So I already [inaudible 00:42:20] the image that night, take a picture, send it, go to sleep and pray that it was accepted in the morning. Or, [inaudible 00:42:29] which is okay, and the way, this is quite a beautiful thing too is that, the way my work schedule was, [inaudible 00:42:37], if I was only doing this I really, it might have driven me mad. If I was only doing this, but I did, I did find a part time job, I worked at a warehouse so it was very mundane, very [inaudible 00:42:52]. But, for that whole time, now that [inaudible 00:43:02]. It gave me a chance to fulfill that visual in my mind, based upon what she said. Sometimes I'd get emails with files that work, check, check the lunch break which was fine. I would check during lunch break and I would see, and it would help, it would just help.

The more she communicated with me, the better it was for me to build that visual. So I build that visual, I built a lot of visuals, based upon that. Um, so I realized with this especially that Joanne's facials weren't going to work, that I really just needed to use his face, use the photographs that we had, were very valuable. You'll see in the book and in the film, that there's a lot of instances where there's um, I'm giving away my process but that's okay, is that, the images that really do look like him were referenced from photographs. If you ever get, there are some images where you can only see the back of his head, or like in action and those are stuff that I had to kind of create myself, but yeah, he, in some cases. Um, I will, I will show this one I was holding so you can see. This, this you can see the difference. Huge difference. Can almost point out, I really captured the youth in him. [inaudible 00:44:29]. No, no -

Joanne: Because we made them think that we went, like which part of the timeline we did everything. Which part it looked like this, for an American -

Dillon: Yes, an American [inaudible 00:44:48].

Joanne: [inaudible 00:44:51].

Dillon: Um, [inaudible 00:44:54]. So this one, you actually see the manuscript. And I call this a sketch, some of you may not, but I'll, I'll quickly show this. To me, that makes a lot of sense [view image]

Dillon: Yes, an American [inaudible 00:44:48].

Joanne: [inaudible 00:44:51].

Dillon: Um, [inaudible 00:44:54]. So this one, you actually see the manuscript. And I call this a sketch, some of you may not, but I'll, I'll quickly show this. To me, that makes a lot of sense [view image]

Joanne: (laughs)

Dillon: To me, that makes a lot of sense. It was very quick, but notice I didn't have to put much to give you an idea of like what I wanted to do. You know when I sent you these sketches, I went through the manuscript [inaudible 00:45:18] and I did some of these before I had the manuscript. My initial idea was, so I was like, "Okay." I'd go through the manuscript, a lot of times I would underline what I thought was most important. What was the, the main focus of that particular thing, what I wanted to do that. So I said, "Okay, this one's about friendship, this is about um, Amanda coming back from New York, and then he came back" [inaudible 00:45:41]. But, um, I want to say that battling this particular frame, I'll show you the photo balling -

Joanne: No.

Dillon: Photo online if some of you are familiar with visuals that try to get them on the power plates, so I was like, you go to Google, you have what? Maybe 100 by 100 resolution, 200 by 200. So try to blow that up is a job [inaudible 00:46:07]. And as you can see, [inaudible 00:46:12]. Can you see his eyes at all? No. It's just completely jagged and flat, where I had to guess. I had to try to depict that and I noticed a lot of times that, coming around with this, if you try to black in the eyes as you see in those photographs, they're just [inaudible 00:46:35]. You know, a little bit possessed and it just won't work. And I think in this whole, Lenox was quite captured, almost there, as you can see, now it's half finished. And I was so messed up, communicating electronically, is that I can do this, take a picture of just this, and say, "Hey Joanne, is this working for you or not?" She'll say, "No, try again." Therefore, not doing the whole thing then going, "What do you think?" Getting, "Oh, no." Which did happen sometimes. I'll get to that also. But, as for the photo quality, wasn't quite there, so therefore, your final that I choose, or that I depicted took me a few tries but I did get John Davis and his face ... There we go. So, that comparison, [inaudible 00:47:31] this was the photo I had to use and I kind of, um, tried to, er, I guess, many times, many times to trace and get his eyes you know -

Dillon: To me, that makes a lot of sense. It was very quick, but notice I didn't have to put much to give you an idea of like what I wanted to do. You know when I sent you these sketches, I went through the manuscript [inaudible 00:45:18] and I did some of these before I had the manuscript. My initial idea was, so I was like, "Okay." I'd go through the manuscript, a lot of times I would underline what I thought was most important. What was the, the main focus of that particular thing, what I wanted to do that. So I said, "Okay, this one's about friendship, this is about um, Amanda coming back from New York, and then he came back" [inaudible 00:45:41]. But, um, I want to say that battling this particular frame, I'll show you the photo balling -

Joanne: No.

Dillon: Photo online if some of you are familiar with visuals that try to get them on the power plates, so I was like, you go to Google, you have what? Maybe 100 by 100 resolution, 200 by 200. So try to blow that up is a job [inaudible 00:46:07]. And as you can see, [inaudible 00:46:12]. Can you see his eyes at all? No. It's just completely jagged and flat, where I had to guess. I had to try to depict that and I noticed a lot of times that, coming around with this, if you try to black in the eyes as you see in those photographs, they're just [inaudible 00:46:35]. You know, a little bit possessed and it just won't work. And I think in this whole, Lenox was quite captured, almost there, as you can see, now it's half finished. And I was so messed up, communicating electronically, is that I can do this, take a picture of just this, and say, "Hey Joanne, is this working for you or not?" She'll say, "No, try again." Therefore, not doing the whole thing then going, "What do you think?" Getting, "Oh, no." Which did happen sometimes. I'll get to that also. But, as for the photo quality, wasn't quite there, so therefore, your final that I choose, or that I depicted took me a few tries but I did get John Davis and his face ... There we go. So, that comparison, [inaudible 00:47:31] this was the photo I had to use and I kind of, um, tried to, er, I guess, many times, many times to trace and get his eyes you know -

10] Okay, pushing on, pushing on, pushing on. Um, I have one last image to show you, speaking of inversely, um, here's a good example of power. I, I was very comfortable with using the photographs that I had and here are some of the original photographs. And also some [traces 00:00:38] of a file I picked out. Um, th- this was a party room where [inaudible 00:00:45] were good friends, where you returned 8, 100% return was always best, [inaudible 00:00:53]. And when you add the image that, that is over here, if I could pause this I'll show everybody, um, once we have this image. Or actually, does it appear lonely or does it not? Just looking at this. Alexis here, does he appear lonely?

Teacher: He appears disappointed.

Dillon: Disappointed. Good. Here, his, his face, his visual, I, I agree that he appears disappointed. But your answer, this is a, just [inaudible 00:01:29] you really wanted to capture that essence of lonely too. And I'll show one more image and then we can get to the um -

Joanne: This also came from a photograph, that I have a really lovely story to tell about but I'm not going to go there. I'm not going to hyperlink to that story.

Speaker 1: Nice. Nice play.

Speaker 2: With Michael, if you want to go there -

Speaker 3: Later on? [crosstalk 00:01:59]

Speaker: I think it might make a difference. Notice the suitcase, notice there's nobody else on the stairs, he is alone in this room. Those are the states provided. All right? See how this small, that little bit of communication and her talking ready to go, "Hey fellas, no I didn't really want to capture this." Every time I look at this, this is really how I feel it. I feel exactly how, how the town [inaudible 00:02:32] in a very uh, well in a not very white town, most, most of the [inaudible 00:02:37] this is kind of more adult.

Dr. Kist: Do you know who took, took this photo?

Joanne: I don't know who took it but I know who's in it, and I met the son of the person standing next to [crosstalk 00:02:52] the original photo, on a bus in Omaha the glass [inaudible 00:02:55], and away from [inaudible 00:02:59]. He sat at the front seat of the bus, I sat at the back seat of the bus. We were the only people in the bus. He was talking to the driver and I said, "Hi." I talked [inaudible 00:03:13]. "Where are you from?" "Trinidad." He said, "Why did you ask?" "Because I hear it in your voice." He said, "I'm doing my best American and you heard Trinidad?" I say, "Yeah, 'cause I try to do American and people know I'm not." So we started talking and I said my name -

Speaker 4: Is this, I believe is this -

Joanne: And he said, "Your name is what?" And I said, "Joanne Kilgour." And he said, "My father was the coach of [inaudible 00:03:55] and he went to [inaudible 00:03:56]."

Speaker 4: Ah.

Speaker 3: That was fun.

Dr. Kist: Unbelievable. Now -

Joanne: Four years later he got his niece to send that picture which has been hanging in his father's living room since 1952.

Speaker 4: Oh.

Joanne: He called his son, he's a dentist, his son is also a dentist, in the [rafter 00:04:17] and said, "Guess who I'm standing next to in the lobby of the Hilton?"

Dr. Kist: Wow.

Joanne: And then he said, "You know that picture grandpa has in his living room, hanging on the wall next to the door? When I was [inaudible 00:04:36] in that picture." His daughter is standing here.” That's why I said, the whole experience has been a divine revelation.

Speaker 4: That's is a powerful, that's a powerful image.

Joanne: People love this and I love how Dillon and I negotiated how it should read, why the most are really important. I knew he had to be alone and Dillon knew, because he's an artist who works in color, that the door had to be black and the windows had to have curtains closed.

Dr. Kist: That's interesting, you don't know anything about art right? I mean I know you're an art person but you don't know other things. [crosstalk 00:05:21] And also [Dillon] what do you know about words?

Dillon: That's a great discussion into the whole idea of multi-modal is that, if she didn't get art she would not be able to communicate to me what she wants. [crosstalk 00:05:37].

Speaker 1: With words though too, if you had an analogy, you had [inaudible 00:05:41] and see it correctly.

Dillon: And that's where our collaboration worked so well. Is that she had the power to give . . . what she looking for and from there, and then, I had the power to perceive and then create it, I, and make it into a, you know, make it something that's visual, that we can see. And I think our, our working in that was the best part, the part that made this successful, because if she didn't she would just say, "Well the transcript's done. It's your responsibility."

Joanne: Which is what publishers do. They send the manuscript to an artist in their stable. You never communicate with the artist. Every time we have presented and there is a writer in the audience or illustrator, they are so blown away by the fact that we are a unit, we see ourselves as right brain and left brain, working together and we talk about the relationship and making this come to life. This is not done in publications. People are, they're like, "What?! You know the illustrator? Talk with the illustrator? You have a relationship with the illustrator?" How can you not? We keep telling students, a picture is worth a thousand words and I have said at the National Library in Trinidad, I wrote the story in 10,073 words. Dillon contributed 25,000 words with the pictures. That is how [inaudible 00:07:25].

How cooperation, and this is what our students have in all our textbooks that work, they're not visual, they are print. So you go to e-book, you're promoting e-book, that is what you're promoting. But they go back and forth from these two forms rather than [crosstalk 00:07:46].

Dr. Kist: Also with graphic novels, I've heard, seen stories with writers script doesn't, since the script -

Joanne: Just write a script.

Speaker 4: You know the artist conceptualizes it by [him]self.

Speaker 3: By yourself.

Speaker 4: Yeah.

Joanne: Which is a kind of litmus test, like if they can make it speak without their input then they really have it. Does that make sense?

Dillon: Well, that's what I was kind of getting at, is that, I remember when we saw that presentation of that, uh, the [inaudible 00:08:14 Presentation of the Olympic athlete in Fairlawn].

Speaker 3: Yes.

Dillon: And while we were sitting there we were talking about, well she had worked with six other artists like you said, and a lot of them, a lot of artists have a problem with personal input.

Dr. Kist: I thought that too, artists, they tend to think that, "I'm the artist, you're just whatever. I understand this not you." Now -

Speaker 4: Put your own spin on it.

Dillon: Right, right, right put your own spin, do that. And me, I thought I was, less of the ability to separate this type of professional practice and it's my responsibility to depict what Joanne wants. This is her project and I'm here to illustrate what she wants. Not just, you know, I'm the artist and you don't understand anything. That's what [inaudible 00:09:05]. And I, I told her that, artists do need outlets, artists need to create and when you want to create you add influence and at a time where I was depicting things to her, I did keep a personal practice, I like light, I was [inaudible 00:09:25] so that therefore I had my outlets, that was my personal practice, but yeah, over here there was still this this [patent 00:09:38]. Which I had got into, so that, that kind of plays with like multi-modal power play characteristics [inaudible 00:09:40] that a lot of people like to have on label. It's not only this, right, but, if I opened up and said, "Well sure, I can do this for you, why not, I'll [inaudible 00:09:52]."

Dr. Kist: You know what this reminds me of, it's almost more now it gets to film making.

Joanne: It is film making.

Dr. Kist: It is film making because, you know, film is film, the director of the film does have more input into [inaudible 00:10:10] the visual artist has to pay attention more to what the director says.

Dr. Kist: It almost sounds like more the director -

Speaker 3: I was thinking it too.

Speaker 1: The producer -

Speaker 3: I was thinking that [inaudible 00:10:28] I know you [inaudible 00:10:30] -

Speaker 1: Okay.

Speaker 3: [inaudible 00:10:31] I know people are interested in a long time.

Speaker 1: Okay.

Speaker 3: Um, so thank you so much.

Speaker 1: Yes, thank you.

Joanne: Um, my film maker couldn't be here. He's on his honeymoon. I didn't write his name on because he went [inaudible 00:10:49] the world premiere of the film.

Dr. Kist: What is this, could you explain what this is?

Speaker 3: So [inaudible 00:10:57] has returned, [inaudible 00:11:00].

Dr. Kist: This is the final book? [books are being shared with the teachers]

Joanne: This is the final book. For the [inaudible 00:11:10]. So I wanted to digress through those, as I showed you on the screen, we were going to read to you but because of time we are not.

Dillon: If I could say one quick thing. How do those relate to those? Um, it kind of relates back to Joanne's discussion on form and the way in which you want to, you notice each of the pages are a different color, I mentioned color before.

Speaker 3: Yes.

Dillon: Which I think is important. Color, color has no [inaudible 00:11:44] and if you go to the final page that has the [inaudible 00:11:48], this picture [inaudible 00:11:49] there's, there's, the color is very dull compared to the rest of the book, it's very colorful.

Joanne: Okay so, this er, [inaudible 00:12:04] is a film maker and he works at [inaudible 00:12:04 in Cannot] and he was recommended by one of my students, I tell you I'm on the gravy train. So my students fill me in and just like I didn't go on the internet and look at the [inaudible 00:12:16 Dillon's work], the recommendation was enough for me to hire him. I did not go on the internet and look at his work as a film maker. I took the recommendation because these are people I have taught, these are people who have been in my company for more than three years. So that said, READ MATT MC COMB'S ARTIST STATEMENT:

I had no idea what to expect when I turned up at [inaudible 00:12:37] to meet with her, and the illustrator Dillon [inaudible 00:12:43 SEDAR]. I walked into a living room covered in art work from the book and two artists, passionate about the project that I soon would be joining possibly. [inaudible 00:12:52] explained who they are, read the story aloud, and so all the pieces come together in my head.

I saw all the scenes, I felt all the emotions [inaudible 00:13:07] when that scenario finished I stood quietly for a few minutes staring at the artwork, visualizing how the film could come together. I knew right then and there this was a story I wanted to be a part of. The story of [inaudible 00:13:22] is inspiring to anyone with a vision for his or her rights. [inaudible 00:13:27] can be overcome with hard work, persistence, and quality relationships. It specifically spoke to me and my personal journey, for in the film and gaming industry. And it will speak to others on their own journey to achieving their dreams. And so you have the film by Max Cole and illustration by [inaudible 00:13:51] narration -

Dr. Kist: Is this still online?

Joanne: I have not put it online.

Dr. Kist: It's on DVD?

Joanne: Correct.

DVD and we're hoping [inaudible 00:14:00].

Dr. Kist: You're not putting it online?

Joanne: We're not putting it online

Speaker 4: Sounds like [inaudible 00:14:24].

Speaker 3: [inaudible 00:14:25].

Speaker 6: [inaudible 00:14:27] hero, [inaudible 00:14:30]'s story. THE FILM BEGINS PLAYING.

[You can view the film on KSUTube.]

TO BE CONTINUED . . .

Teacher: He appears disappointed.

Dillon: Disappointed. Good. Here, his, his face, his visual, I, I agree that he appears disappointed. But your answer, this is a, just [inaudible 00:01:29] you really wanted to capture that essence of lonely too. And I'll show one more image and then we can get to the um -

Joanne: This also came from a photograph, that I have a really lovely story to tell about but I'm not going to go there. I'm not going to hyperlink to that story.

Speaker 1: Nice. Nice play.

Speaker 2: With Michael, if you want to go there -

Speaker 3: Later on? [crosstalk 00:01:59]

Speaker: I think it might make a difference. Notice the suitcase, notice there's nobody else on the stairs, he is alone in this room. Those are the states provided. All right? See how this small, that little bit of communication and her talking ready to go, "Hey fellas, no I didn't really want to capture this." Every time I look at this, this is really how I feel it. I feel exactly how, how the town [inaudible 00:02:32] in a very uh, well in a not very white town, most, most of the [inaudible 00:02:37] this is kind of more adult.

Dr. Kist: Do you know who took, took this photo?

Joanne: I don't know who took it but I know who's in it, and I met the son of the person standing next to [crosstalk 00:02:52] the original photo, on a bus in Omaha the glass [inaudible 00:02:55], and away from [inaudible 00:02:59]. He sat at the front seat of the bus, I sat at the back seat of the bus. We were the only people in the bus. He was talking to the driver and I said, "Hi." I talked [inaudible 00:03:13]. "Where are you from?" "Trinidad." He said, "Why did you ask?" "Because I hear it in your voice." He said, "I'm doing my best American and you heard Trinidad?" I say, "Yeah, 'cause I try to do American and people know I'm not." So we started talking and I said my name -

Speaker 4: Is this, I believe is this -

Joanne: And he said, "Your name is what?" And I said, "Joanne Kilgour." And he said, "My father was the coach of [inaudible 00:03:55] and he went to [inaudible 00:03:56]."

Speaker 4: Ah.

Speaker 3: That was fun.

Dr. Kist: Unbelievable. Now -

Joanne: Four years later he got his niece to send that picture which has been hanging in his father's living room since 1952.

Speaker 4: Oh.

Joanne: He called his son, he's a dentist, his son is also a dentist, in the [rafter 00:04:17] and said, "Guess who I'm standing next to in the lobby of the Hilton?"

Dr. Kist: Wow.

Joanne: And then he said, "You know that picture grandpa has in his living room, hanging on the wall next to the door? When I was [inaudible 00:04:36] in that picture." His daughter is standing here.” That's why I said, the whole experience has been a divine revelation.

Speaker 4: That's is a powerful, that's a powerful image.

Joanne: People love this and I love how Dillon and I negotiated how it should read, why the most are really important. I knew he had to be alone and Dillon knew, because he's an artist who works in color, that the door had to be black and the windows had to have curtains closed.

Dr. Kist: That's interesting, you don't know anything about art right? I mean I know you're an art person but you don't know other things. [crosstalk 00:05:21] And also [Dillon] what do you know about words?

Dillon: That's a great discussion into the whole idea of multi-modal is that, if she didn't get art she would not be able to communicate to me what she wants. [crosstalk 00:05:37].

Speaker 1: With words though too, if you had an analogy, you had [inaudible 00:05:41] and see it correctly.

Dillon: And that's where our collaboration worked so well. Is that she had the power to give . . . what she looking for and from there, and then, I had the power to perceive and then create it, I, and make it into a, you know, make it something that's visual, that we can see. And I think our, our working in that was the best part, the part that made this successful, because if she didn't she would just say, "Well the transcript's done. It's your responsibility."

Joanne: Which is what publishers do. They send the manuscript to an artist in their stable. You never communicate with the artist. Every time we have presented and there is a writer in the audience or illustrator, they are so blown away by the fact that we are a unit, we see ourselves as right brain and left brain, working together and we talk about the relationship and making this come to life. This is not done in publications. People are, they're like, "What?! You know the illustrator? Talk with the illustrator? You have a relationship with the illustrator?" How can you not? We keep telling students, a picture is worth a thousand words and I have said at the National Library in Trinidad, I wrote the story in 10,073 words. Dillon contributed 25,000 words with the pictures. That is how [inaudible 00:07:25].

How cooperation, and this is what our students have in all our textbooks that work, they're not visual, they are print. So you go to e-book, you're promoting e-book, that is what you're promoting. But they go back and forth from these two forms rather than [crosstalk 00:07:46].

Dr. Kist: Also with graphic novels, I've heard, seen stories with writers script doesn't, since the script -

Joanne: Just write a script.

Speaker 4: You know the artist conceptualizes it by [him]self.

Speaker 3: By yourself.

Speaker 4: Yeah.